Each Troll Lord release improves significantly upon the last. The Malady of Kings is a noteworthy, high-level D20 adventure.

Review Originally Published May 21st, 2001

PLOT

Warning: This review will contain spoilers for The Malady of Kings. Players who may find themselves playing in this adventure should not read beyond this point.

A thousand years ago, as the Catalyst Wars which would signal the beginning of the Dark Age fell upon the world, Luther Pendegrantz – guided by visions – set sail from his throne in Kayomar. His wife, Vivienne, guided by visions of her own, knew that she would never see her husband again. Luther found his way upon the Sea of Dreaming, and spent a millennium upon those fabled waters before returning to rejoin his old comrades in overthrowing fell Unklar and ending the long Winter Dark which had rested upon the world in his absence.

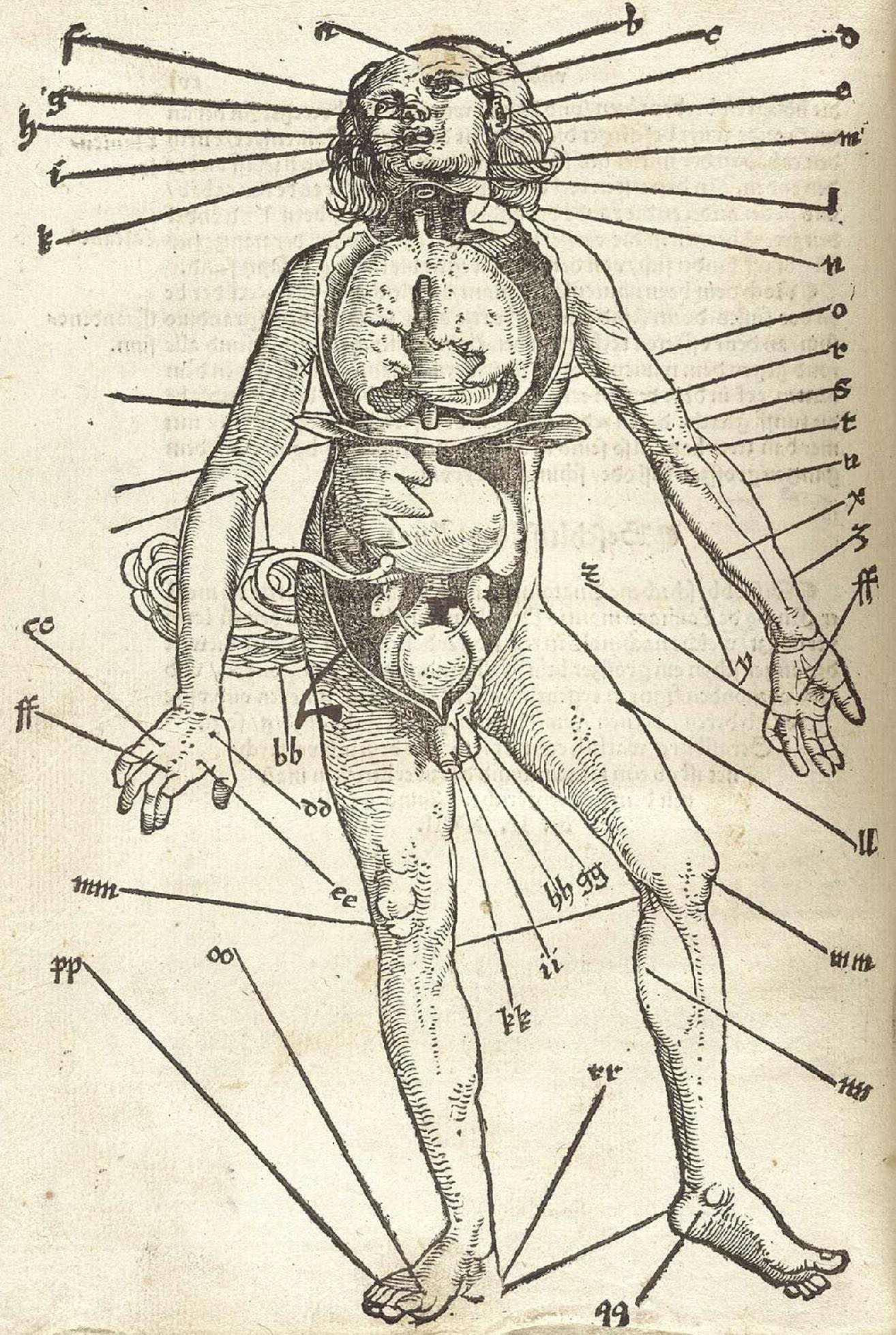

Unknown to Luther, however, Vivienne – his long-lost wife – had not found a peaceful death. Pining for her absent husband, she became one of the undead, haunting the royal sepulcher in which she had been quietly inurned. She remains there still, while her husband – having saved the world and been sainted as St. Luther – retired to the Isle of Blight upon the Sea of Dreaming, from which his order of paladins stands guard over the world. St. Luther has recently fallen under the foul curse of ancient enemies, and has been trapped in a sleep of deep dreams within his castle upon the Isle of Blight.

Enter the PCs: Following ancient clues discovered within the legendary Books of Jaran they track down Frieden Anhohe and the Shrine of the Gallant, the ancient crypt of the Pendegrantz family. There they discover – and disturb – the long-forgotten Vivienne. This sudden psychic disturbance summons the arch-mage Aristobolus – now half-mad, but once Luther’s companion and Vivienne’s dear friend. This in turn, brings forth Daladon Half-elf, another of Luther’s famous companions. Both Aristobolus and Daladon mourn for Vivienne’s current plight, and ask the PCs to aid them in relieving her sorrow by summoning Luther from the Isle of Blight to make peace with his wife.

From here the PCs will sail upon the mystic Dream Horn (provided by Daladon) upon the Sea of Dreaming, finding their way – at last – to the Isle of Blight. Here they will converse with a demi-god exiled from his homeland, and – at last – free Luther from his slumber.

GREAT GAMING ENVIRONMENTS

I’ve said this about every single Troll Lord product I’ve reviewed, and I’ll say it again here: They have really incredible settings. For example, in The Malady of Kings you’ve got:

The Eldwood, a subtly fantastic environment, and utterly memorable. The Eldwood is the oldest forest in the world, and its mysteries are both ancient and well-protected. What separates the Eldwood from every other “ancient forest” of generic fantasy, however, is its unique geography: Its outermost reaches are known as the Rimwald, where travel is easy, the trees are far apart, and a small number of human settlements are sprinkled throughout. As one pushes beyond the Rimwald, however, they come to the Festungwald (“festung being an old dwarf word, literally translated as ‘fortress’”) – a tangle of underbrush, younger trees, and wild animals nearly fifteen miles deep in places serving as an effective natural barrier of protection for the Eldwald, the deep woodland of the forest, with oaks which stand like “monumental buildings”. You know, its a subtle thing – but its small touches like these which distinguish the worlds and settings which are truly memorable.

The Sea of Dreaming, also known as the Dreaming Sea, is – in fact – another plane of existence which lies in coexistence with our own (and, possibly, all others). “The sea is a watery plane of chaos, each drop a physical manifestation of a dream. These droplets of the dreams and nightmares of the living creatures of past, present, and future have accumulated over the millennia to form this great ocean. They are infinite in number, and the Dreaming Sea has no bottom.”

The Isle of Wintery Dreams, built by the foul demon who ruled over the world during the Dark Age as a way of corrupting the world of dreams, the Isle of Wintery Dreams remains – inhabited by fiercesome Dream Warriors.

And, finally, the mystical Isle of Blight, where St. Luther rests and rules.

PROBLEM AREAS

When I first started reading The Malady of Kings I was somewhat concerned by the fact that this adventure – unlike Troll Lord’s others – depended very heavily upon the idiosyncratic elements of the After Winter Dark setting. I felt there was a very real possibility that the only way this adventure would be playable was if you were playing it on the World of Erde.

Fortunately, I was pleasantly surprised to discover just how easily this module could be adapted. St. Luther, for example, can be replaced with any ancient hero of your campaign world that might still be alive (and trapped in a magical sleep) – or he could even be a minor noble of some sort. The settings themselves can be transferred fairly easily – swapping villain for villain and hero for hero. The adventure as it stands is of epic proportions – building upon the central mythology of the After Winter Dark campaign setting – and you can certainly maintain that by bending the mythology of your own world. But nothing stops you from toning down the epic elements to a more manageable degree (with little more than some simple name changes).

The only element which could pose serious problems is the Sea of Dreaming. Truthfully, this can be added to any campaign world (and would, in my opinion, be a worthy addition). But it may, of course, have no position in your person cosmology. Again, this is easily worked around: Simply place the Isle of Blight somewhere on a normal ocean in your campaign world. (You only lose one small, and relatively unimportant, scene this way.)

Other than that, I only found a handful of minor problems: Chenault describes one encounter as being of EL 19. While technically accurate (the wizard in the encounter is, in fact, 19th level), it should not actually be described as such (if you were to reward the PCs for defeating the wizard, as the EL rating implies, you would do horrible things to game balance). In some places the boxed text (generally very evocative) trips over the line into poor melodrama and amateur histrionics, which is unfortunate.

The setup and adventure hooks for the adventure are also, in my opinion, underdeveloped. I would have liked a little more detail on why, specifically, the PCs should get interested enough in the passages regarding the Shrine of the Gallant in order to go looking for it. As it stands you have little to no sense for how the PCs get involved in the plot.

There are also a couple of points where you can tell this is an adventure which saw its inception as something which the author ran for his own play group (preserved, most noticeably, in areas where the plot briefly seems to follow the logic his players took, rather than the possibilities which other DMs may face).

These are minor problems, however, and do not noticeably detract from the overall quality of the adventure, or – more importantly – its usefulness.

CONCLUSION

Each new release from Troll Lord Games improves upon the last: Content, lay-out, boxed text, art, maps – the whole nine yards. If they continue along this course, it shouldn’t be long before they’re turning out material rivalling the quality of Penumbra, Green Ronin, and Necromancer.

The Malady of Kings, specifically, is an excellent adventure for 10th level characters. This is a point in a campaign where truly epic themes typically begin to creep into the game, and The Malady of Kings addresses this need perfectly.

Style: 3

Substance: 4

Authors: Stephen Chenault

Company: Troll Lord Games

Line: D20

Price: $7.00

ISBN: 0-931275-01-7

Production Code: TLG1601

Pages: 40

For an explanation of where these reviews came from and why you can no longer find them at RPGNet, click here.